|

Recent research suggests that certain technologies introduced over the past two centuries exhibit very predictable rates of advancement, becoming more efficient — and thus cheaper — at a steady clip. And solar energy is one of those technologies. Looking into the past can give us a glimpse of the future.

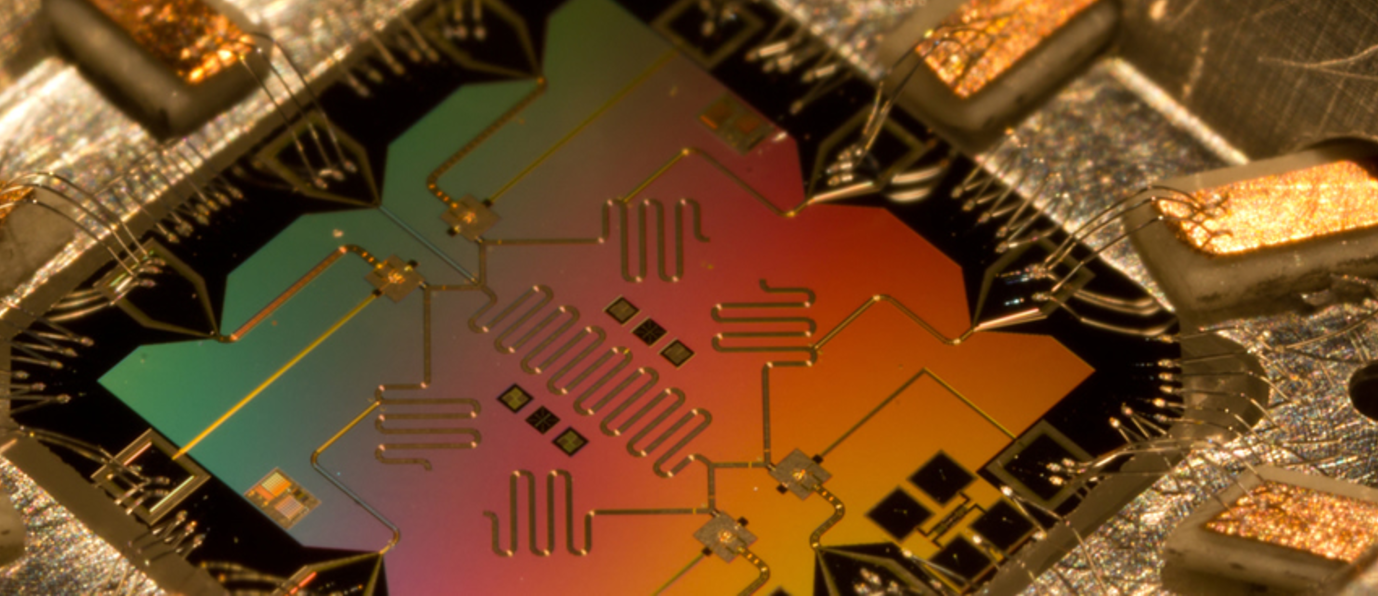

IEEFA.ORG — In 1965, Gordon Moore, one of the founders of chip giant Intel, noticed that the number of transistors per integrated circuit doubled every two years on average, with corresponding advances in speed and declines in cost. This quickly became known as Moore’s Law. In the succeeding half century, Moore’s Law has held up, with the cost of computing power plunging dramatically over the years. Last year, two economists named J. Doyne Farmer and Francois Lafond published an intriguing paper that riffed off Moore’s Law. “Many technologies,” they correctly observed, “followed a generalized version of Moore’s Law” in which “costs tend to drop exponentially.” Some technologies, however, do not follow this model, and it can be hard to distinguish between them. Past performance, in other words, is not always predictive of future results. In order to sort out the ones that follow a version of Moore’s Law from the ones that don’t, the researchers engaged in an interesting thought experiment. They selected 53 very different technologies across a range of sectors and built a deep database of historical unit costs for producing milk; sequencing DNA; making laser diodes, formaldehyde, acrylic fiber, transistors, and many other things; and electricity from nuclear, coal, and solar. They then engaged in a statistical method called “hindcasting.” This entails going back to various points in the past for each technology, taking whatever trend existed at the time, and then extrapolating it into the future. They then took this “prediction” and compared it to what actually happened. This has the virtue of actually testing the predictive power of the data rather than fitting the data to a model. Moreover, it gives some insights into the accuracy of future forecasts. After all, the authors note, a skeptic who looks at the trends in the cost of solar and coal “would rightfully respond, ‘How do we know that the historical trend will continue? Isn’t it possible that things will reverse, and over the next 20 years coal will drop dramatically in price and solar will go back up?’” Hindcasting offers a way to answer that question in quantitative terms. And the answers are rather interesting. The researchers found that many technologies don’t follow a robust version of Moore’s Law, even if the cost per unit can fluctuate a great deal in the short term. The cost of chemicals, household goods, and many other goods don’t stay the same, but they fluctuate in a random fashion, going up for a number of years and then going back down again. Others, like transistors, DNA sequencing, and others, are eerily predictable. Energy, on the other hand, is a mixed bag. The current unit cost of coal is approximately the same as it was in the year 1890 in inflation-adjusted terms. It has, however, fluctuated randomly over time by a factor of three, exhibiting short-term trends that eventually reverse themselves. The same is true of gas and oil. Nuclear has also fluctuated, but is actually more expensive now than when it was first introduced in the 1950s. In short, there’s no equivalent for Moore’s Law when it comes to fossil fuels and nuclear power. Which brings us to solar. Here the trend has been unmistakable, with the price per unit dropping a very steady 10 percent per year. This has been a very rapid decline with little variability. Despite changes in demand, the ebb and flow of government subsidies, solar has steadily dropped in cost. This very Moore-ish trajectory permits us to make reasonably secure predictions about the future cost of solar power. There’s a very slim chance those predictions could be wrong, but compared to predicting the cost of coal — which is akin to spinning a roulette wheel – we can get some glimpse of the future. And that future will almost certainly be dominated by solar — not because it’s “green,” but because it’s cheap. Indeed, the authors’ data suggests that there’s a fifty-fifty chance that solar will become competitive with coal as early as 2024; there’s a good chance that could happen even sooner. Indeed, it already has in some countries. In the near future, it will likely be the coal industry that will need subsidies to compete with solar, not the other way around.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

James Ramos,BPII'm your go to solar energy expert here to guide you step-by-step through all of your solar options. Categories |

James The Solar Energy Expert

RSS Feed

RSS Feed